Watts Up?! The 62nd CicLAvia is upon us this Sunday, and The Militant is here as always to highlight you on some points of interest along the 6 1/4-mile route! We return to The City Community of Good Ol’ Watts for the 7th time (the last time was the May 21, 2023 CicLAmini along 103rd Street and Central Avenue down to 109th Street). This route combines that route with some of the previous Watts-oriented routes, minus the 103rd Street stretch, and the very northern end of the route between MLK and Washington Boulevard was last used in the December 3rd, 2023 route that was mostly down Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard.

As you may or may not know, this route was originally planned for June 22nd but was cancelled due to El Hielo being a potential party pooper. This Sunday’s Watts route was eventually re-scheduled to September 14 but at the cost of a planned CicLAmini in San Pedro (at least we got a longer route this time), though that one will have to take place next year or later – so we will only have seven CicLAvias in 2025 (assuming the rest go on as scheduled…you never know in today’s world…).

As usual — Happy CicLAvia, Go Dodgers, Go Rams, Go Trojans or Bruins, Go Galaxy or LAFC and see you or not see you on the streets!

Oh yeah, if you found this Epic CicLAvia Tour guide useful and visit any of these sites, please add the #EpicCicLAviaTour hashtag to any social media post that includes it. The Militant will be glad to re-tweet!

And if you appreciate The Militant’s work, kick him a little love via PayPal! He *hates* asking for money, but you know how it is these days…A Militant’s gotta pay his bills! He sacrifices a lot of his time to do this, so your support is much appreciated!

To support The Militant Angeleno: https://www.paypal.com/donate/?hosted_button_id=K5XC5AM9G33K8

The Militant would like to thank Joe Ryan and Chris Barrow for their generous support this Summer to keep this website alive!

1. Lincoln Theater

1926

2300 S. Central Ave, South Los Angeles

From 1927 to the 1950s, this Moorish Revival theatre, designed by John Paxton Perrine, featured the finest live entertainment by Black performers, to a predominantly Black audience (though notable White folks like Charlie Chaplin dug it as well). It was even nicknamed the “West Coast Apollo” during its heyday, which featured the likes of Duke Ellington, Nat King Cole and Billie Holliday gracing its stage. In 1962 the building was purchased by the First Jurisdiction of the Church of God in Christ and remains a house of worship today, this time as the the Iglesia de Cristo Ministries Juda. The Lincoln Theater building was designated as a City of Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument in 2003 and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2009. Though it appears disused, the theater’s history continues, as in February 2023, it was named as one of 40 sites in the U.S. to receive $3.8 million preservation grant by the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund.

2. Second Baptist Church

1926

2412 Griffith Avenue, South Los Angeles

Built around the same time as the Lincoln Theater is this building that has always been a church. But it’s one building that’s rich in African American history. It was the host venue for the NAACP’s national conventions in 1928 (the first-ever on the West Coast), 1942 and 1949. In 1962, Malcolm X spoke at a meeting held at the church. And Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. himself spoke here in 1964 and 1968 — the latter appearance, just two weeks before he was martyred in Memphis, Tennessee. To top it all off, this Lombardy Romanesque Revival building was designed by none other than famed African American architect Paul R. Williams, who designed many buildings around Los Angeles, most notably this one. This building is also designated as a City of Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument (1978) and was likewise added to the National Register of Historic Places (2009).

3. Masjid Bilal Islamic Center/Site of Elks Lodge

1929

4016 S. Central Ave, South Los Angeles

This mainstay of the local Muslim community since 1973 also has a deep history in the local Black community. The original building was originally built in 1929 as the home of the local Elks club. But it was no ordinary Elks Club (who discriminated against Black membership). It was run by the Improved and Benevolent Protective Order of Elks of the World, an African American-run organization founded in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1898 that functioned as a fraternal order for people of color. Though obviously not directly affiliated with the white Elks club, it is run with the otherwise identical customs and traditions, and with nearly half a million members worldwide, is the largest black fraternal organization in the world. A new mosque building, fronting Central Avenue, has been under construction since 2019, which features the tallest minaret in California.

4. Ralph J. Bunche House

1919

1221 E. 40th Place, South Los Angeles

The Central Avenue corridor was home to Los Angeles’ Black community, primarily due to the racial covenants that restricted them from owning homes elsewhere in the city. But great things can come from places of injustice. Ralph J. Bunche was a teenager arriving with his family from Detroit, by way of Ohio and New Mexico, who attended nearby Jefferson High School and went to UCLA, graduating as the valedictorian at both schools. He went on to Harvard, where he earned his Ph.D in Political Science (the first African American to receive a doctorate in PoliSci from a U.S. university), and later was one of the founders of the United Nations. In 1950, due to his diplomatic work in the negotiations that ended the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, he won the Nobel Peace Prize — the first non-White person to ever win the esteemed award (Come to think of it, we could use his expertise right now…). And he once lived right here, just two blocks east of the CicLAvia route.

5. Site of Black Panther Headquarters

1969

41st Street and Central Avenue, South Central Los Angeles

Nooo, this isn’t where Wakanda is. The northwest corner of 41st Street and Central Avenue wasn’t just the Los Angeles headquarters of the 1960s-era Black Panther Party (that’s some real Militants right there), but in a time where the names Mike Brown and Eric Garner have been fresh on the minds of people, it was the site of a significant event in the tumultuous history of relations between the black community and the Los Angeles Police Department. On December 8, 1969 — 45 years before the day after CicLAvia — police officers arrested a number of people on that corner for loitering, which eventually escalated into a four-hour armed confrontation. The LAPD used a previously untested paramilitary unit during the raid, which was called the Special Weapons And Tactics unit, or SWAT. Four LAPD officers and four Black Panther members were seriously injured during the shootout, but miraculously no one died. The building that housed the headquarters was demolished in 1970.

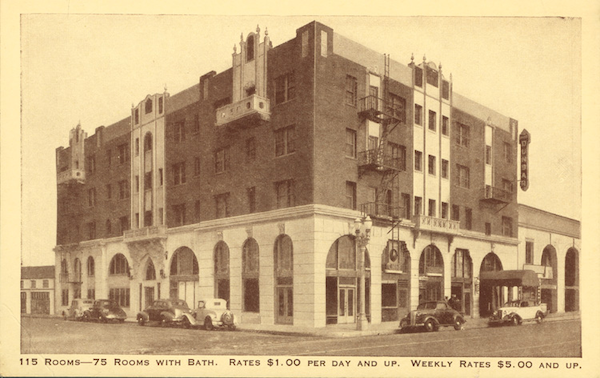

6. Dunbar Hotel/Club Alabam

1928

4225 S. Central Avenue, South Central Los Angeles

Built in 1928 (then known as the Hotel Somerville, the only hotel in Los Angeles at the time to welcome Black people) as the primary accommodations venue for the 1928 NAACP national convention at the nearby Second Baptist Church, The Dunbar is one of the few remaining physical symbols of the Central Avenue of yesteryear, the hotspot of all that is jazz and blues. In the perspective of Los Angeles music history, Central Avenue in the 1920s-1950s was the Sunset Strip of the 1960s-1980s. And perhaps even more. A nightclub opened at the hotel just a few years after its opening, and legends such as Count Basie, Cab Calloway, Lena Horne and Billie Holliday. Next door was the Club Alabam, another one of the most popular jazz venues on Central Avenue. Known for its classy image and celebrity clientele (both Black and White), legends such as Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker and Miles Davis graced the stage. Today, the Dunbar Hotel building serves as an affordable housing complex for seniors.

7. South Los Angeles Wetlands Park/Site of Los Angeles Railway South Park Shops

2012/1906

5413 S. Avalon Boulevard, South Central Los Angeles

Head west on Metro’s brand-spankin’ new 5.5-mile Rail to Rail Bike Path along the Slauson Corridor, and ride a couple blocks north on Avalon Boulevard to visit this relatively-new park space, which opened in 2012 and was covered by The Militant on his blog right after its grand opening. Previously the site of the sprawling South Park Shops, it was a major facility for storing, maintaining and repairing transit vehicles, used from 1906 to 2008 by the Los Angeles Railway, the original Los Angeles Metropolitan Transit Authority, the Southern California Rapid Transit District and today’s Metro (ride around San Pedro Street nearby for Yellow Car track cracks in the street!). After the transit facility was retired, the brownfields were re-purposed as a nine-acre public open space that features native plant landscaping (yessss!), a lagoon that functions not only as a bird habitat, but as a natural stormwater cleaning facility. A LACMA satellite museum space was originally planned at the park, but the museum scrapped the plan last year.

8. Los Angeles Railway U Line

1920-1947

Central and Slauson avenues to Vermont Avenue and Manchester Blvd via Downtown Los Angeles

Central Avenue hosted not one, but two Los Angeles Railway Yellow Car lines in different locations along the CicLAvia route. One of them was the U Line, which originated west of here, at two different branches on Vermont and Manchester and another at Western and 39th. They met near Exposition Park and ran through the USC campus (one of the reasons for the “U” in the line name) and northward onto Downtown Los Angeles before heading back south on Central Avenue and ending at Slauson. The line ran until 1947.

9. Augustus F. Hawkins Natural Park

2000

5790 Compton Ave, South Los Angeles

Make another short detour a few blocks east of the CicLAvia route on the 5.5-mile Rail to Rail Bike Path along the Slauson Corridor

and you’ll find another one of the best-kept secrets in South Los Angeles — Augustus F. Hawkins Natural Park, an 8.5-acre surreal green oasis in the ‘hood, featuring ponds, native plants, hiking trails, picnic areas and even wildlife. This former DWP pipe yard was converted into a re-created natural park (named after the late African American congressman who represented the area for 28 years) in 2000 by the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy, which trucked in actual dirt from Malibu mudslides to the site to form the park’s terrain. The park is popular with local residents seeking refuge from urban life, and the park is also popular with members of the local Audubon Society, who frequent the park to do bird sightings and bird counts.

10. The Beehive

2019

961 E. 61st Street, South Los Angeles

Originally part of the Goodyear Tire & Rubber factory campus until 1979 (more on this next), this cluster of industrial buildings was renovated and adapted by SoLa Impact as an Opportunity zone project and in 2019 became The Beehive, a dynamic Black-owned event venue campus intended for hosting commercial spaces, events and functions for small businesses and organizations. Many are already familiar with The Beehive as the location of the popular Black Market Flea events.

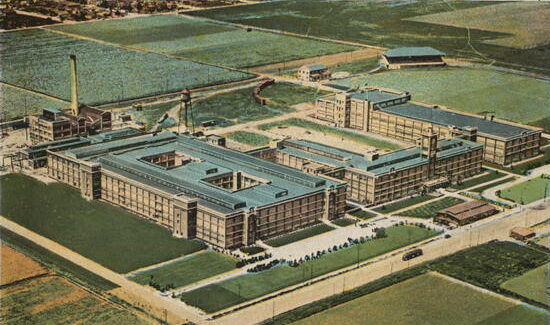

11. Los Angeles Central Post Office/Site of Goodyear Tire Factory

1984/1920-1979

7001 S. Central Ave, Florence-Firestone

In 2008, The Militant visited this ginormous USPS facility, with the numerical designation as the very place where the western ZIP codes begin. Most of Los Angeles’ mail gets processed through here, which means letters or packages mailed through here will get sent out of town faster (since they have to come through here anyway). The post office facility opened relatively recently, in 1984, as part of a redevelopment project for the massive parcel, whose previous life was that of the Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. California factory, which existed from 1920 to 1979.

Automobile tires and other rubber products were manufactured here for nearly 60 years, and early versions of the iconic Goodyear blimp once had its own hangar at the southwestern corner of the lot. But wait — there’s even more history on this lot: nearly two decades before the tire plant opened, this was the home of Ascot Park racetrack, which opened in 1903. The ornate design of the early 20th-century hippodrome inspired the aesthetics of another So Cal racetrack – Santa Anita Racetrack in Arcadia, which opened four years later and still exists today.

12. Los Angeles Railway S Line

1920-1963

Santa Monica Blvd & Western Avenue to Central Avenue & Firestone Blvd via Downtown Los Angeles

Central Avenue’s other Yellow Car line was the “S” line, which ran in many different configurations through the years, but most of its life it ran from Santa Monica & Western in East Hollywood through Downtown (like nearly all Los Angeles Railway lines did) and down to Central and Firestone. The picture to the left depicts a Yellow Car in 1963 (then painted green in the old Los Angeles Metropolitan Transit Authority’s colors) running by the old Goodyear Tire factory! The line was discontinued (along with many of the other surviving Yellow Car lines) on March 31, 1963 – the final day of rail transit in Los Angeles until the Metro Blue Line (now the Metro A Line) opened on July 14, 1990.

Look for the ivy-colored concrete building sitting in the middle of a paved lot on the southeast corner of 85th and Central – that’s one of the remnant structures of the Los Angeles Railway’s streetcar loop terminal station, located at that very lot!

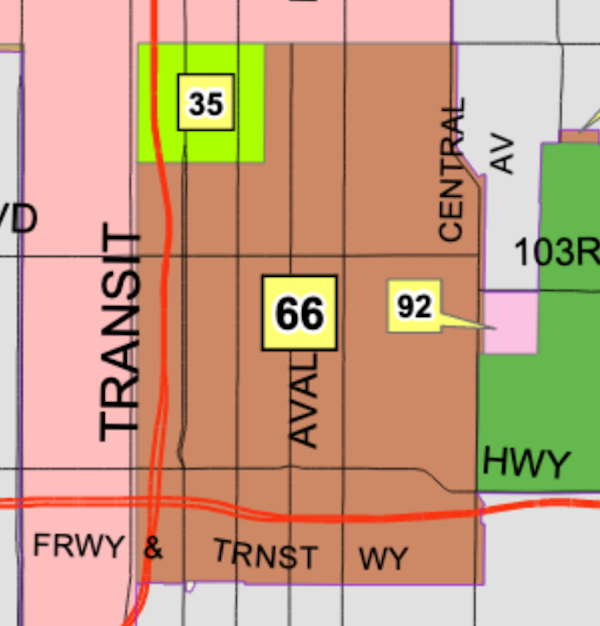

13. Green Meadows Diagonal

1926

Central Avenue between 92nd and 95th streets, Green Meadows

As you ride on the CicLAvia route along Central Avenue, the road makes a seemingly arbitrary diagonal jog between 92nd and 95th streets. Why is that? Well, if you know your Los Angeles history, many non-grid street alignments follow the boundaries of ranchos, properties/land parcels, and legacy cities/towns that were lost to annexation. The latter was the case here, as an unincorporated farm town called Green Meadows sprung up here circa 1887. True to its name, it was a rural settlement with artesian wells, alfalfa fields and apple orchards. The northeast corner of the town featured the diagonal notch, and when the town was finally annexed into the City of Los Angeles on March 18. 1926, the boundary was incorporated into the city street grid and Central Avenue was forced to follow suit. The name Green Meadows was re-claimed in the early 2000s and given to the portion of South Los Angeles where the old town once existed. So now you know!

14. Ted Watkins Memorial Park

Dedicated 1995

1335 E. 103rd Street, Watts

Originally built in the 1930s to memorialize Western actor Will Rogers, this 28-acre Los Angeles County park was re-named in 1995 after the late Ted Watkins, a local community activist and the founder of the Watts Labor Community Action Committee, which he started in 1965, just months before the Watts Riots. The aftermath of the rebellion heightened the purpose of his nonprofit agency, which dealt with social services, community development and empowerment for the Watts area. The park also features a youth baseball field built by the Los Angeles Dodgers, a newly-built community swimming pool and gym with basketball courts.

15. Watts Central Avenue Great Streets Project

2023

Central Avenue between Century Blvd and Imperial Hwy

You may or may not have noticed that one of the “hidden agendas” of CicLAvia is to create or improve bicycle infrastructure on the streets of its routes. The “Heart of L.A.” routes during the 2010s birthed the existing DTLA bicycle infrastructure on 7th Street, Spring Street and Broadway. The streets of Watts have hosted six previous CicLAvias and this 1.1-mile LADOT Great Streets project, spearheaded by the Watts Labor Community Action Committee to alleviate the high number of car crashes along the thoroughfare, became the end result. Completed in February 2023, it features protected bicycle lanes along Central Avenue between Century and Imperial Highway.

16. WLCAC Skate Park

2010

10950 S. Central Ave, Watts

Conceived in 2006 as a project of local nonprofit Watts Labor Community Action Center (which is headquartered on-site in the surrounding 7-acre campus) and skatepark builder Spohn Ranch, this 4,000 square foot skateboarding facility was created to give Watts youth a safe and quality space to ollie. If you brought your board to CicLAvia, you have just the place to channel your inner Tony Hawk.

17. Pacific Electric El Segundo/San Pedro Branch

1911

The railroad track that crosses Central Avenue just south of the southern terminus of the CicLAvia route is the El Segundo/Torrance branch of the Union Pacific Railroad, which emerges from the track that parallels the Metro A Line just south of the 103rd St/Watts Towers station. But this track has quite some history. It carried Pacific Electric interurban cars from Downtown Los Angeles and on to El Segundo (1911-1930), Redondo Beach (1912-1940) and San Pedro (1912-1940). After 1940, the tracks were used for local freight trains of the Southern Pacific Railroad until it merged with the Union Pacific in 1996. The plate girder bridge to the west of Central Avenue may or may not have been a Pacific Electric relic (The Militant won’t add it to his Pacific Electric Archaeology Map until he can confirm it).

18. Compton Creek

Running from Main Street & 107th St to the Los Angeles River

Just to the west of Central Avenue is Compton Creek, the southernmost tributary of the Los Angeles River. It is a remnant of a time when what is now South Los Angeles and the South Bay were dotted with wetland marshes replenished by winter rains and underwater aquifers, surrounded by forests of Willow and Cottonwood trees. In fact, the unincorporated Los Angeles County community known as Willowbrook was named after what the creek originally looked like. Originally called “Avila Creek” (after the family that owned the original Rancho La Tajauta, which became the Watts/Willowbrook area), The creek began in a onetime marsh in South Los Angeles, where its source was forced into an underground channel circa 1940s and emerges east of South Main St near 107th Street. Passing its namesake city, the creek heads southeasterly and joins the Los Angeles River just east of the 710 and south of Del Amo Blvd. Like its destination waterway and other creeks in Southern California, this 8.5-mile arroyo was channelized in the 1940s to function as flood control (although the southernmost 2.7 miles still have a natural bottom, providing an important ecosystem for avian, aquatic and reptilian wildlife).

You must be logged in to post a comment.