DAY 1: MONDAY, MARCH 4, 2024

There are many places outside of the Los Angeles metropolitan area that virtually all Angelenos seem to have some sort of common connection to: The Grapevine, Kettleman City, Coachella, Mammoth, Zzyzx Road, Las Vegas…just to name a few. But there’s one place this historically-geeky Militant has held in a special, almost mystic regard his entire life: The Owens Valley.

Many of us have heard the phrase, “Los Angeles stole its water from the Owens Valley.” But that phrase asks more questions than it answers: Where is the Owens Valley, exactly? And how do you actually steal water? Do you like, drive a bunch of tanker trucks in the middle of the night and siphon water out of a lake while nobody’s paying attention or something?

The Militant has always wanted to visit this Owens Valley place since he’s heard of the phrase. So finally, in early March of 2024, his curiosity caved in and The Militant decided to make a road trip there for the very first time. Now, The Militant doesn’t travel much outside of his native Angeleno environs (…or maybe he actually does, and he just doesn’t tell anyone when he’s out of town/state/the country…), and he hasn’t publicly left the Los Angeles Metropolitan Area since toting along his bike on an Amtrak Pacific Surfliner trip to San Diego back in 2008. Prior to leaving, The Militant did some research via the web and books, and consulted some of his trusted Operatives, some of whom go there fairly regularly for the purposes of hiking, fishing or finding peace of mind.

PRIMER TIME!

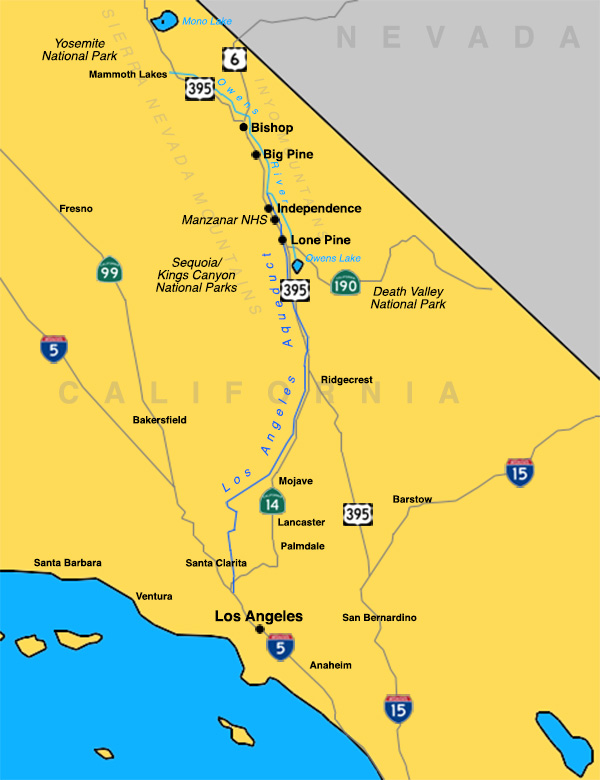

The Owens Valley is a 100ish mile-long, deep and narrow desert valley in the eastern side of California (a.k.a California’s Back), nestled between the majestic Sierra Nevada Mountains on the west and the more geologically-interesting and almost as majestic Inyo-White Mountains on the east. It forms the southeastern section of what is known as the “Basin and Range” region of North America between the Pacific Coast and the Rocky Mountains, which is comprised of alternating valley basins and mountain ranges (And remember, outside of SoCal, the mountain ranges run north-south!). It was named in 1845 after Richard Owens (or was that Richard Owings?), one of John C. Fremont’s trusted guides in his exploration parties (though Richard was not a part of Fremont’s exploration of the area and had never actually set foot in his eponymous valley during his lifetime). Where you’d have a valley, there’s usually a river, and the OV has two of them: a natural river called the Owens River, which has existed since the Ice Age, and an artificially-built parallel watercourse known as the Los Angeles Aqueduct, built in 1913 by the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (more on this later…).

The area also has some sort of identity crisis: To this day, the valley’s name rarely appears on maps, and there is very minimal, if any, signage in the area referring to the OV as a geographical entity. Instead it is known by many different names: The indigenous Paiute people, who has made their home there for at least the past 6,000 years, calls the area “Payahüünadü” (the land of flowing water). The local tourism industry (and even the DWP itself) refers to it as the “Eastern Sierra” (And that’s “Sierra” (singular) and not “Sierras” (plural) – the locals hate when us “flatlanders” do that). A local museum describes the region as “Eastern California.” Authors have also dubbed it the “Deepest Valley” or “The Land of Little Rain” (it gets 5.6″ of average rainfall annually, making it a true desert).

WATER WARS, EPISODE I: THE URBAN MENACE

Okay, okay, time to address The Elephant in the Room. The intellectually lazy will just drop the “Forget it Jake, it’s Chinatown” quote and leave it at that, but it’s much more complex than that (and that the 1974 motion picture was only a heavily-fictionalized version of history that didn’t even line up chronologically with the actual Water Wars – the movie took place in the late 1930s and depicted a very urban Los Angeles that already benefited from an imported water system, whereas the real Water Wars of the 1900s-1920s took place when Los Angeles only had 300,000 or so people and was still primarily agricultural outside of the city proper.

Much has been written about this, so The Militant will summarize: Ever since the Ice Age, when snow was even more abundant in the Sierra Nevada and Inyo Mountains than it was last Winter, when the snow melted, it descended down the mountains into local creeks and joined the Owens River, which emptied its contents into Owens Lake. Since there was much more snow to melt, the lake was many times larger that it was in the early 1900s. For generations, the Paiute tribes even designated an elder as the tuvaiju – the head irrigator – whose responsibility was to dig channels from the creeks to the villages – micro-aqueducts, if you will. Life was good in Payahüünadü. Until the white settlers from the East arrived in the mid-1800s and found the area conducive to farming and cattle grazing. So they did The Colonizer Thing, drove out most of the Paiute and dug their own water channels to steal that Sweet Sierra Snowmelt from the Paiute villages and into their ranches.

In the late 1800s, some 200 miles to the south, a man named Fred Eaton was head of the Los Angeles City Water Company (the private utility company that became precursor to today’s DWP), whose city of 102,500 was growing at an extraordinary rate (the population was only 50,000 in 1890). He personally hired a self-taught Irish immigrant engineer named William Mulholland to be in charge of digging zanjas (water canals) from the Los Angeles River to serve the growing city. But by the time Eaton had become mayor of Los Angeles in 1898-1900, the Los Angeles River was reaching its limits a far as the primary water source and Mayor Eaton, who took a camping trip to the Owens Valley, wondered about that Sweet Sierra Snowmelt flowing from Owens River into Owens Lake and envisioned an aqueduct taking that water on a gravity-propelled trip 200 miles south to Los Angeleeze. During Eaton’s term, voters passed a bond measure that allowed the City to purchase the private Los Angeles City Water Company, and the DWP was born. In the mid 1900s decade, the City government decided to build an aqueduct from the Owens Valley and Mulholland became the Chief Engineer of the project. Though no longer mayor, Eaton purchased land in the Owens Valley from the ranchers – and sold it to the City of Los Angeles for the aqueduct project – a move that, though not illegal, was of a questionably ethical nature. Construction of the Los Angeles Aqueduct began in 1908 and was completed in 1913. During the Aqueduct’s dedication ceremony on November 5, 1913 – with 10 percent of the entire population of the city at the time in attendance – Mulholland (though not the original visionary behind the aqueduct, he was the de facto face of the project during the Second Industrial Revolution era where the celebrities of the time were scientists, inventors, industrialists, architects and engineers (like Mulholland) – remember, this was a time when there were no rock stars, or even movie stars yet…), made a speech consisting of all but five words:

“There it is, take it.”

The Owens Valley ranchers, feeling deceived by Eaton at losing their properties and livid at the City of Los Angeles for taking their water rights had the sand kicked in their face – literally – when Owens Lake, once one of the largest lakes in California, was rendered into a dry lake bed due to the lack of water from the Owens River feeding into the lake. The dry lake plus the valley’s notorious high winds created unprecedented dust storms that created visibility and health problems for the residents of the valley.

Begun, The Water Wars have.

For as long as The Militant can remember, The Militant has known that crazy fun water slide on the east side of the 5 freeway in Sylmar was the Los Angeles Aqueduct. But he always wanted to know what the other side was like. So 110 years after it opened, The Militant decided to find out for himself.

The Militant Angeleno was going to the Owens Valley – to see the other side of the Aqueduct, both literally and figuratively. And channel his inner Huell Howser and explore the California’s Gold of the nearby environs.

DRIVIN’ UP THE 395

The Militant left on the afternoon of Monday, March 4. It’s 200 miles to Lone Pine, he’s got a full tank of gas, half a pack of Trader Joe’s Multi-Seed Tamari Soy Sauce Rice Crackers, it’s almost dark…and he’s wearing sunglasses.

Hit it.

The drive is like the usual drive up the 101 to the 170 to the 5 to the 14. Antelope Valley traffic is a thing, though, and the 14 can be a slog. Imagine doing this every freaking workday (They should just take Metrolink instead…they expanded AV line service after all). The trek between Santa Clarita and Palmdale is tedious and at times The Militant questioned why he decided to take this trip in the first place. But once the road curved north and the Antelope Valley was in view, and after crossing the San Andreas Fault cut between the Pacific and North American tectonic plates, the traffic seemed to exponentially fade. By the time he crossed the Los Angeles-Kern County border, traffic was basically nonexistent and everyone went 80MPH.

Next was the town of Mojave, a railroad town famous for fast-food joints, gas stations, Borax-hauling mule teams, airliner graveyard, wind turbines (with eerie oscillating red air beacon lights) and MacOS 10.14. But after The Militant made a right turn after the railroad crossing, he ventured into unknown territory, veering into the desert where darkness afforded you nothing but road signs (bearing curiously exotic names like “Jawbone”) and the tips of sagebrush illuminated by car headlights. After climbing in elevation through Red Rock Canyon State Park (no, not that one) and surviving the scary-ass single-lane-in-each-direction stretch of the 14, in the distance to the east, some city lights can be seen. It’s the city of Ridgecrest, a landlocked Navy town (there’s a Naval Weapons Station next door), famous for a couple big earthquakes that hit during the 4th of July weekend in 2019. Then the 14 ends and assimilates into the lifeline of the Owens Valley: US 395, a 1,305-mile national highway that runs from Hesperia through the Owens Valley, to Reno, NV, then back to California before going through Oregon and Washington, and ending at the Canadian border (Hmmm…end-to-end road trip one day?).

ALL UP INYO BUSINESS

The Militant also transitioned from familiar Kern county to unfamiliar Inyo County (the 2nd largest county in size in the Golden State, yet the 7th smallest in population (18,829) – smaller than the city of Hermosa Beach or the Los Angeles community of Jefferson Park). The Owens Valley, threaded by the 395, is the cultural and economic center of Inyo County.

After a couple hours in total darkness, signs of civilization finally popped up: working gas stations, a beef jerky stand, some roadside restaurants, some motels/inns, especially one shaped like a lemon. For someone familiar with traveling north along the 5 or the 99 through the San Joaquin Valley, it was certainly odd, yet undeniably charming, to see business front the highway without having to make an exit.

With the speed limit dwindling from 70 to 25 MPH and the 395 taking on the name, “Main Street,” The Militant finally pulled into the town of Lone Pine (pop. 1,484), which, despite its diminutive size, was a relative bastion of urbanity, with streetlights, shops, a museum, local eateries, a McDonald’s, a Carl’s Jr., a taco truck and a stoplight. Without exiting, The Militant turned right into a parking lot and checked into the Dow Villa Motel, a century-old inn founded in the 1920s by local residents Walter and Maude Dow, which boasts of once having famous Hollywood Western film stars like Roy Rogers, Gene Autry and John Wayne as guests. The nearby Alabama Hills, a series of tan-colored granite rock formations located between the town and Mount Whitney, was the hotspot location shoot for numerous Western flicks back in the day (as well as more contemporary films like Tremors and Iron Man).

There was nothing much to see at night; The Militant was perhaps the only one on the streets and it wasn’t even 10 p.m. Just behind the businesses were the residential neighborhoods, which were mostly single-story homes, with a few two-story structures. There’s a high school just south of the motel. It seems like you could walk through the entire town in 15 minutes. The Militant just chilled the rest of the evening in his room. The cable TV channels, oddly enough, had local Los Angeles channels – yep, KCBS, KNBC, KTLA, KABC, KCAL, KTTV and KCOP. It’s almost like The Militant didn’t really leave home. Or maybe this was a simulation. To be fair, there were a couple of “local” stations on the tube – one station based in Reno, Nevada (KOLO) and another in Mammoth Lakes (KSRW). No SportsnetLA though (booo!)…but seeing as he wanted to have the odd satisfaction of being far away from Los Angeles, seeing familiar channels was a bit off-putting.

Pulling into the Owens Valley at night is like having blindfold over your eyes. He couldn’t wait until sunlight lifts the veil to reveal what this place has to offer…

To be continued in Part 2: The Highs and Lows of Inyo County

You must be logged in to post a comment.