DAY 2: TUESDAY, MARCH 5, 2024

Good morning from Lone Pine, California! The Militant woke up to this sight this morning:

He had never seen anything like that before. Seeing tall mountains to the west. And not just tall mountains, but tall, snowcapped mountains. And not just tall, snowcapped mountains, but the highest peak in the Lower 48 states and in the state of California. That’s right, Mt. Whitney, all 14, 505′ of her, was standing right there. No, not there – the tallest peak to the eye was actually Lone Pine Peak (12,949′) to the left (a lot of people ID it wrong), but that’s only because it’s situated closer to Lone Pine. Whitney is higher, but further back to the west, looking more like a sawtooth-shaped wedge with grooves cut in it than a classic prominent mountain. The Sierra’s grey granite form was coated irregularly by white snowpack, sprinkled like a delicious sugar-topped pastry. This was the first time The Militant had ever saw Mt. Whitney with his own eyes, and what a sight to behold.

The Militant was here to explore and to check out this Lone Pine place. At first he was looking for the town’s namesake solo tree, only to discover that it was destroyed in a flood decades ago. The town was first settled in the early 1860s. In the early morning hours of March 26, 1872, the town got a rude awakening when an earthquake estimated to be M7.8 rocked the Owens Valley and killed 27 residents and destroyed 52 of the town’s 59 adobe and brick buildings. The quake also created a permanent scarp to the north of the town and a new lake to the south called Diaz Lake, which is used for camping, fishing and recreation today. But the 1870s were just the beginning, as the town became an important trading and transportation hub for the local gold and silver mines via railroad lines and ferryboat routes that used to traverse the once-navigable Owens Lake. During the late 1900s and early 1910s decades, Lone Pine housed many of the workers who built the Los Angeles Aqueduct, which led to the town’s first Hollywood casting call in 1920, when a silent western film called The Roundup was shot on-location in the nearby Alabama Hills (named during the Civil War era not after the state per se, but after the Confederate battleship the CSS Alabama). In the 1920s, the motion picture industry, the private automobile and the paved highways US 395 and US 6 linked Los Angeles and Lone Pine even closer together. Since then, the Alabama Hills and the Sierra Nevada backdrop have portrayed the Himalayas (Gunga Din, 1939), Afghanistan (Iron Man, 2008) and various generic locales in the American West. The Museum of Western Film History on the south side of town highlights the various motion pictures, television shows, music videos and commercials that were shot in the area.

Today Lone Pine is a major hub for recreation and tourism in the Owens Valley and serves as the gateway to both the highest and lowest points in the continental United States: Mount Whitney and Death Valley National Park’s Badwater Basin (282′ below sea level), respectively. The Militant got to see the highest point, now it was time to check out the lowest!

WELCOME TO CHILLVILLE

But first, breakfast! The Militant walked across Main Street from his motel to find an incredibly chill small town, where time seemingly goes by slower than normal. He first noticed it this morning when he actually had to wait for the snooze alarm to go off. That just does not happen whenever The Militant is back in Los Angeles! The decidedly urban Militant is simply not used to this much chillness. It’s odd, exotic, yet somewhat…satisfying, all at the same time. There are lots of businesses with that serif-heavy “Western” font. It’s a little silly, yet also cute and charming. Like is this really The Old West, or is Lone Pine just playing up to its Movie Western image? Or is it both?

Just down Post St., just a few yards from Main St. was The Alabama Hills Cafe, a quaint little small-town eatery where locals and tourists alike come in and have breakfast or lunch (they close at 3 p.m.). There’s country music playing on the sound system and the walls are adorned with framed paintings of Mt. Whitney and illustrations of the cafe’s namesake hills nearby. The Militant had the simple but classic Sausage Patty & Eggs breakfast ($14.50), which also came with home fries, toast and unlimited coffee cup refills. There was also a glass display of various pastries, cakes and cookies but The Militant did not partake. The breakfast was good enough for him.

Walking down Main Street, The Militant found a solitary bus stop next to the McDonald’s. Odd, since it was located on Gene Autry Lane and not the main thoroughfare. But indeed it was the only transit stop in town. It’s where Eastern Sierra Transit‘s buses stop in town. They don’t make other stops in town, but rather stops in other towns. Looking at the schedule on the wall, their service comprises of one bus line going north all the way to Reno, NV(!) which takes six hours and only runs once a day; another line running between the Metrolink station in Lancaster and Mammoth Lakes (three hours to Lone Pine, five to Mammoth) and another between Lone Pine and Bishop (an hour and 15 minutes’ trip). Wait, why is The Militant already thinking of taking a transit trip here?

Speaking of connections to Los Angeles, he saw his first DWP truck in the area, parked across the street. It was surreal. They’re the same white trucks with the Los Angeles City Seal on the doors. But here the Militant was, 200 miles north of home. Soon enough, he saw more of them roll through Main Street. A hundred and ten years after the Los Angeles Aqueduct was built, The LADWP still looms here. Not just for Aqueduct maintenance, and not just for electric power generation and services (many of the towns here are DWP customers just like we are(!), but also for these two mind-blowing facts: 1) The DWP owns 490 square miles of land in the Eastern Sierra region, which includes the Owens Valley and some of the Owens River watershed area north near Mammoth Lakes and Mono Lake. To put it in perspective, the City of Los Angeles proper is 469 square miles. Which means the DWP owns more area here than the entire size of Los Angeles; and 2) The DWP is the second-largest employer in the Owens Valley (the largest is the County of Inyo government). But apparently the colonial entity’s gotta look over the water (and power)…

Down the street was the Museum of Western Film History. It looked closed, as the parking lot was seemingly empty, but later on The Militant found out that it was indeed open (Open daily 9 a.m. to 4 p.m.). He’s got a busy schedule today so maybe tomorrow (or for that transit trip back here)…

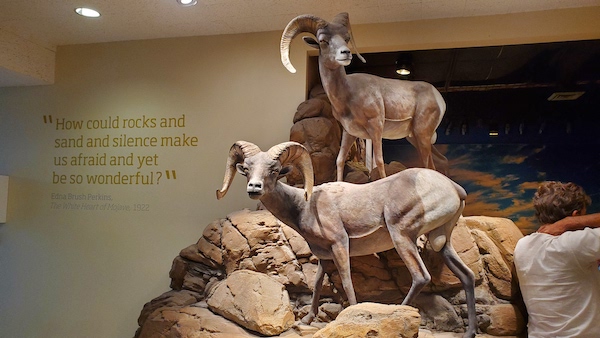

The Militant proceeded to the extreme south end of Lone Pine, where US 395 meets the 136. It’s where the Eastern Sierra Interagency Visitor’s Center is – a facility featuring informative displays on the area’s environment, wildlife and history that also includes a gift shop, a native plant garden (woo-hoo!) and a desk where people can purchase passes for various recreational uses in the area (i.e. hiking Mt. Whitney). The center is jointly run by the National Park Service, the U.S. Forestry Service, the Bureau of Land Management and the Eastern Sierra Interpretive Association. And, of course, there’s an LADWP presence in the form of a 3-D relief map of the Eastern Sierra and Southern California showing the course of the Los Angeles Aqueduct and the DWP’s related electric generation and reservoir facilities. There’s also a section of Aqueduct pipe on display.

OWENS’ SLAKE

Speaking of the 136, that’s where The Militant headed on his way to his next destination: Owens Lake. Well, you couldn’t actually get up to the lake, as, despite the fact that the lake contains more water than it has in recent memory (due to last year’s record snowmelt), there was still a couple miles’ worth of desert sand, dry brush, salt deposits and gravel (installed by the DWP as part of their court-mandated mitigation measures to reduce dust storms on the lake) between The Militant and the shoreline. He was standing on a lookout point along the 136, which is on the eastern side of the lake, and the water is on the west side (Wesssssoiiiide!) of the lake. Still, if The Militant had one of them time travel DeLoreans with him and went back in time to 1910, the shore of the lake would probably be just a few yards away from him (Of course, The Militant would run the risk of disrupting the space-time continuum by holding his smartphone and taking photos and videos). Still, it was an opportunity to see Owens Lake in a somewhat liminal state, witnessing the effects of the DWP’s desiccation, while also looking upon a large swatch of water coverage area.

Continuing on the 136, The Militant passed by the nearly-ghost town of Keeler (pop. 71), once a more bustling town that, back in the late 1800s, had a steamship port that transported silver ore from the nearby Cerro Gordo Mine above the town in the Inyo Mountains, as well as a railroad station. Unfortunately, The Militant sped by it and couldn’t stop in time to pull over and take a gander. Instead, he proceeded southbound, and the highway became the 190. Soon, Joshua Trees were appearing in the landscape, and at some point in the area, a very famous Yucca brevifolia once stood, which adorned the back cover of a certain Irish rock band’s album in the ’80s. Unfortunately, there’s no signal out here, so The Militant’s trusty Google Maps app was of no use. Moving on!

DEATH VALLEY DAY

The Militant was successful in reaching his destination for the day: Death Valley National Park. He had heard so much about this place growing up, back when it was just a mere National Monument and shooting location for Star Wars. Yet, he never had the opportunity to come here, until today. Well, the day has come at last, and he set an entire day to see the sights. Home to the Timbisha Shoshone people, Death Valley NP is actually made up of a number of valleys in an area larger than the state of Connecticut(!). It’s the largest U.S. National Park in the Lower 48 states. Its morbid moniker originated in 1849 when a group of prospectors on their way to get summa dat California Gold crossed the valley and got lost. One of the members of their party perished. By the time they found their way, as they left the area, one of them wrote in their journal, “Farewell, death valley,” and the name stuck. It was designated as a federal National Monument in 1933, and it earned its full-fledged National Park status 30 years ago, in 1994.

As the 190 started meandering, a very picturesque canyon came into view. A vista point with a parking lot afforded the view of the canyon, called Rainbow Canyon, and a valley below – Panamint Valley (the southwestern-most of the Death Valley valleys). The gorge is nicknamed “Star Wars Canyon,” not because any of those movies were filmed at this location, but because of the Air Force and Navy fighter jets that make this their regular training exercise routes (resembling the X-Wing fighters zipping through the Death Star’s trenches). One dude was hanging out with a telephoto lens-equipped camera, looking intently at the circular airplane contrails in the sky. He told The Militant that he had been waiting there for the past 20 minutes to catch one of those planes, so he can take a photo of the plane flying below him. The Militant obviously wanted to see such a sight, but after hanging around for 10 minutes with no jet fighter swooping by, he wished Photographer Dude good luck and went on his way.

Next came a never-ending, winding descent down to Panamint Springs, the first of a handful of “villages” within the national park. It contained a restaurant, a motel, an RV park and a gas station (important, since you obviously don’t wanna run out of gas here). The 190 became a straight road through Panamint Valley, as the snowcapped Telescope Peak rose above it (The Militant will eventually get to the other side of that mountain). Speeding through the narrow valley, there were pools of water on the desert floor – remnants of the last rainstorm which came by in February. Before he knew it, the road climbed in elevation and rode up like a ribbon towards the Panamint range, where more winding roads (though not as tightly curved) lay ahead. Navigating though Towne Pass, the road had a gradual long descent, broken up by occasional undulating topography, into the actual Death Valley.

The Actual Death Valley was a broad, flat basin of tan and white, surrounded by mountains in various shades of brown. Above was blue sky semi-concealed by high clouds – this was truly the Big Sky Country The Militant had heard about in regards to the American West. Majestic and very scarcely populated – there were maybe only a few hundred human beings within that tan and white basin, which stretches for 3,000 square miles (to put it in perspective, the Antelope Valley is of equivalent size but is home to over half a million people).

The next habited village here was Stovepipe Wells, which had similar amenities as Panamint Springs, but was somewhat larger; with a larger hotel, restaurant, general store and campground (one can easily smell – guided by the desert winds -the aroma of barbecue grilling from the campers nearby). It was here The Militant went to a solar-powered kiosk, stuck his credit card in and got his National Park pass ($30 per vehicle). It’s needed if you plan to park or stay at the national park and is good for seven days. A sign directed him to a ranger station several yards up the road where they gave you a Death Valley map if you showed them your pass. The ranger was also nice enough to put some Scotch tape at the top and bottom of his receipt-like pass so that he can stick it on his car window.

Just two miles up, The Militant got to visit Arakis (or Tatooine). The Mesquite Flat Sand Dunes are one of a half-dozen sand dune areas within Death Valley, but perhaps the most popular and accessible – the 190 runs right though here and most of the other dunes require a 4×4 journey on a long dirt road). People are even allowed to bodyboard down these dunes, which reach up to 200 feet high. The Militant had never been to a desert sand dune before so this was pretty damn exciting. He even removed his combat boots because why not? The sand was soft and the dunes were dotted with their namesake Mesquite Trees. It was like walking on a beach with no ocean. This was also the perfect time of year to go to Death Valley as the temps were only in the mid-70s. The wind was strong, as the dunes would never exist without them, but not unbearable. You got the perfect view of this Big Sky Country, with nothing but the sound of the wind.

Next was the third village area and the heart of Death Valley, Furnace Creek, which also had the usual campground-store-gas station-motel amenities. But for the latter, there were two rather large resorts – The Ranch at Death Valley and the palm-lined and pretty swanky-looking The Inn at Death Valley. But Furnace Creek was home to the park’s main visitor center and iconic thermometer (Furnace Creek recorded the world’s hottest temperature of 134º F in July, 1913). And yes, people come here in the heat of Summer just to take selfies with the thermometer. Fortunately, today only registered between 74º and 76º.

The visitor center had educational, interactive displays on the park’s climate, environment, history and wildlife. There’s also the obligatory gift shop, park ranger info desk and even a theatre/lecture room where educational presentations, workshops and talks take place as part of the park’s programming.

Continuing on south along the 190, was Zabriskie Point, a popular vista to capture Badwater Basin, the adjacent badlands area and the Panamint Mountains to the west. There’s hiking trails down to Golden Canyon down below, but time is of the essence (this trip was made the week before Daylight Saving Time kicked in) and he had to move along. But the trail signs point to an area below called “Gower Gulch,” which amused The Militant since it’s also the name of a Western-themed shopping center at Sunset and Gower in Hollywood. The Militant wondered whether this was the same “Gower,” but upon further Militant Research, the Hollywood Gower Avenue/Gulch was named after farmer John T. Gower, and this Gower Gulch was named after the unrelated Harry P. Gower, a Borax miner who was the original owner of Death Valley’s Ranch and Inn resorts. Yes, The Militant is all about geeking on these historical tidbits.

A bit south of Zabriskie Point was the 2.5-mile dirt road loop through Twenty Mule Team Canyon, a dusty badlands area famous for the location shot from the Star Wars sequel Return of the Jedi where the droids C3-P0 and R2-D2 brave a Tatooine desert wash en route to the palace of Jabba the Hutt. The Militant may or may not have found the palace, and cannot reveal whether he was acosted by a group of Gamorrean Guards, or threatened by Boba Fett himself. At least you all know he survived being thrown into the Rancor pit. Bo shuda!

Heading back towards Furnace Creek was a bit of an adventure as road maintenance caused traffic to temporarily be stalled to allow Caltrans crews to do their thang while vehicles were escorted in caravans of 15 or so vehicles each way as only one lane was open to traffic.

Speaking of A Galaxy Far, Far Away, another filming location lay ahead in the road towards Badwater Basin, just below Zabriske Point. Golden Canyon was the locale in the original 1977 Star Wars movie where the Jawas stalked R2-D2. The Militant didn’t have much time to hike through here, as he, too, was afraid those little hooded scavenger critters might kidnap The Militant. Safety not guaranteed!

There was another Star Wars locale ahead – Artists Drive – where Luke Skywalker was mugged by Tusken Raiders and saved by the wise Jedi, Obi-Wan Kenobi. But the sun was already setting over the Panamint Mountains, so we’ll have to skip that one.

But The Militant’s final destination was getting closer – Badwater Basin, which had been filled to nearly unprecedented amounts of H2O from last year’s voluminous rainfall and unexpected Tropical Storm Hilary, as well as this Winter’s rains. The basin was even referred to by its retroactive Ice Age identity, “Lake Manly.” Some people were even fortunate to have been able to kayak the basin, and The Militant was hoping to have had that opportunity, but alas, yesterday, the national park announced that water levels have dropped to where that was no longer feasible. Boooo. But still, this was a unique opportunity to see the basin with water (albeit merely a foot deep), as opposed to the desiccated salt flat that visitors normally see.

The Militant finally pulled into the Badwater parking lot, which was nearly full of vehicles. Opposite the road was a tall cliff face of the Black Mountains and a sign placed 282 feet above that read, “SEA LEVEL.” This was it! The Militant had reached the lowest point in North America! There were over two dozen people who went out to the water and decided to wade. The Militant removed his combat boots yet again and scrunched into the wet surface of salt and sand. Yards ahead the water got to ankle-deep, and later shin-deep. The bottom was coarse but gave way when he walked on it. The evening sky bore shades of gold and periwinkle and shades of purple and grey in the distant clouds. The reflection of the Panamint Mountains and its highest point, Telescope Peak (11,043′) appeared in the glistening water. It was calm and peaceful and the other two-dozen-plus people wading in Lake Manly likely shared the same exhilaration. The Militant almost didn’t want to leave, but the darkening sky was the invisible bouncer that told the visitors, “You don’t have to go home but you can’t stay here.” The Militant waded back to shore, walked barefoot on the boardwalk and cleaned himself with some paper towels in his car. There were white salt rings halfway up his lower legs which he wore as a badge of honor for the rest of the evening.

Now came the hard part. Driving in Death Valley at night afforded nowhere the same visual thrills as driving during daylight. Aside from the villages and passing autos, it was virtually pitch dark. H back-tracked alone Badwater Road back to the 190. At Stovepipe Wells he gassed up for the long trek back to Lone Pine. He had to climb the long incline up Towne Pass and wind back down to Panamint Valley. This was a drive not for the faint-hearted (or drowsy). But halfway through Panamint Valley, The Militant pulled over, got out of his car and looked up at the sky. Death Valley is recognized as an International Dark Sky Park, devoid of urban light pollution and tonight was a moonless and generally cloudless night (which got a lot colder than the mid-70s of the daylight hours). Towards the western sky, The Militant could recognize the Orion constellation – but not the typical vertical bowtie of seven stars that you can see from the city – rather the entire constellation! His arms, his club, his shield. And to the right was a bright dot that was the planet Jupiter and a group of stars that formed the Pleiades star cluster. He wish he brought his telescope along, but the naked-eye view was breathtaking enough – he could see the stars in between the stars! Even though he was unable to take any pics of this, this was probably the greatest memory of his Death Valley visit (the Lake Manly wading was a close 2nd though and the dunes #3).

In due time he got back into his ride, climbed back up towards the west end of the park and zipped back into the Owens Valley where he returned to Lone Pine. To celebrate his trek, he had a pint or two at the local drinking hole – Jake’s Saloon. Yes, a real Western saloon, though it looked a little more urban inside with neon lights and rock music playing in the background. He looked down on the salt rings on his legs and reminisced about the amazing sights and experiences that he had today.

Most of all, he got to set his eyes upon the highest and lowest points of the Golden State, all in the same day.

To be continued in Part 3: Independence Days

One thought on “The Militant’s Epic Owens Valley Adventure, Part 2: The Highs and Lows of Inyo County”

Comments are closed.